This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Drilling deeper into Data as the new Oil

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes, 51 seconds

It’s become so common place over recent years, to talk of ‘data as the new oil’, that it’s easy to not hear it anymore. To not notice when it’s used, nor think of the implications such an analogy brings.

However, this week, an image and an article have prompted me to think deeper about this topic. I’m glad I did, as the analogy holds up and prompts consideration of aspects that need to be considered. If data is to have as big an impact on our shared economy as oil has had, we best be prepared and think about the implications for us and our businesses.

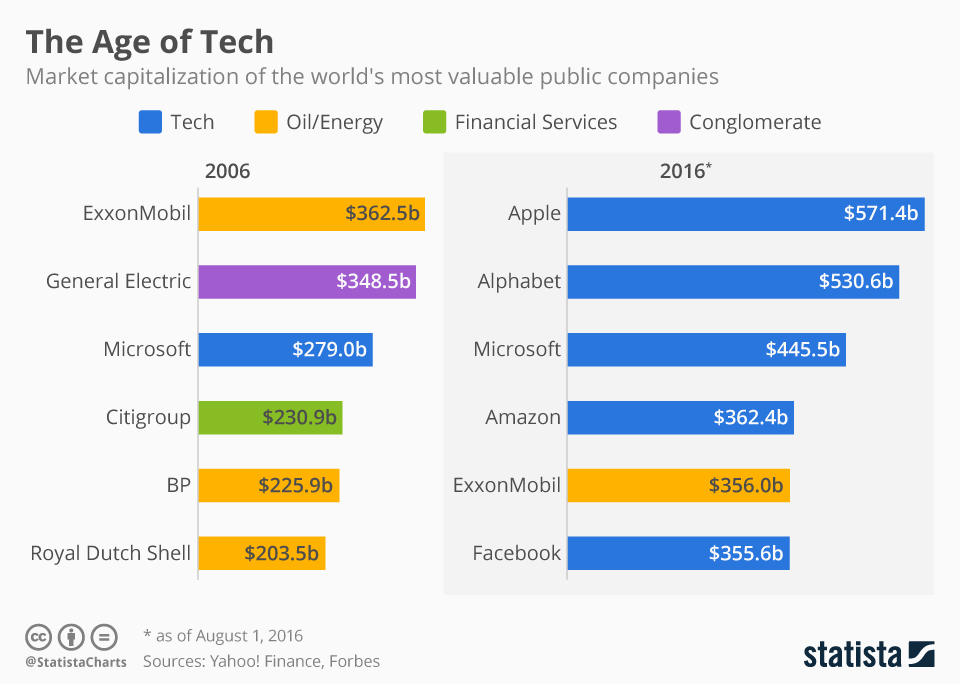

The first prompt was an image I’d seen previously, but made the rounds on Twitter once again. It compares the top 6 companies (by market capitalization) from 2006, with the top 5 for 2016. It’s telling to see 2 major oil companies drop out of that list and it now be dominated by 5 business that are data businesses as much (or more) than they are technology firms.

But the more substantial prompt for my reflections was a great article in a recent copy of the Economist magazine. Entitled “Fuel of the Future” it reviews how the new ‘data economy’ is shaping up. That review is structured by comparing how data will fuel the economy of the 21st century, when considering how oil fuelled the 20th century economy.

Lots of really telling points are made by taking this tour from the standpoint of an economist, so I thought I’d share the key lessons I took away from reading it.

Data is unlike any previous resource

It might sound counter-intuitive to begin with a difference, but considering how oil and data are both drivers of growth and change bring us here. Technological developments in our ability to extract oil and data both led to new infrastructures, new businesses, new monopolies and new politics. However, compared to oil, data does not have a limited supply.

Data is extracted, refined, valued, bought and sold in different ways. Because of this fact, it will change the rules for markets and demand new responses from regulators. GDPR will not be the final world in trying to bring order to the ‘wild west’ of data exploitation. Crucially it also has immense and growing scale. Research firm IDC predict that data created and copied each year will reach 180 zettabytes by 2025 (180 followed by 21 zeros).

The growth of the Internet of Things and Big Data also means the quality and formats of data will be more diverse. Keeping pace with continued generation of data, whatever we do, will continue to be a challenge, even as technology and machine learning race to keep pace.

Size matters in today’s Data Wells

Just as the oil barons carved up the majority of the oil supply (in the days of the infamous TV series “Dallas”), so too today, it is the data ‘majors’ who own a disproportionate amount of data. Firms like Facebook and Google pump from bountiful reservoirs, as their millions of users post or like content, as well as search for everything they need.

This is already impacting valuation of these businesses, in a similar way that new of potential new oil fields raised the value of yesterday’s oil majors. Consider Uber being valued at $68bn, that is partly because it owns the pool of data about supply (drivers) and demand (passengers).

But what of the innovation wave of recent years? Data-driven start-ups are like the ‘wildcats’ of the oil economy. Innovative start-ups will continue to create new data and prove the potential of new technology to derive value from data. Unlike the oil business, it is also easier for non-technology firms to enter this market. This thinking underpins our business model at Brainnwave, giving these wildcats a single place to go and find the data resources will accelerate innovation.

Expect to continue to see such innovation and diversification as businesses explore the potential of data. However, just as has happened for years in the oil markets, expect to also see the bigger data firms takeover the successful smaller ones.

Pricing challenges mean a lack of standardized Markets

Unlike oil, data does not yet have thriving standardized markets, trading mostly happens in organized silos. One of the reasons for this is the opaqueness of pricing data. Data is not a commodity. Each stream of data may have different quality and relevance to different customers. There is a disincentive to trade, as each party is worried about getting ripped off. The Brainnwave marketplace is acting as the honest broker enabling data producers to reach new markets and data consumers to trust the data they are accessing.

Researchers have begun to develop pricing methodologies, what Gartner calls ‘infonomics’, for example when Caesars Entertainment filed for bankruptcy, its most valuable asset was deemed to be its data (valued at $1bn).

But for firms with deep pockets, the difficulty in picking apart the value of just buying certain data, make it easier to just buy data producing businesses. Hence the history of Facebook buying WhatsApp ($22bn), Intel buying Mobileye ($15bn) and Microsoft buying LinkedIn ($26bn). Data contracts are tricky, easier to buy the “data field and the pipeline”.

Beyond GDPR, further challenges for the TrustBusters

Given the principles outlined in the EU’s new data protection regulation (GDPR), it was perhaps a surprise that the EU did not block the merging of Facebook and WhatsApp. Despite its pledges not to, Facebook is now merging both user bases. So, one of the battlefronts for privacy campaigners is to upgrade competition legislation, as is happening in Germany. After all, oil magnates came to see their need to be accountable to increasingly powerful environmental regulation, as it became more robust.

A good rule for regulators may be to be as inventive as the companies they are there to police. Ezrachi and Stucke, authors of ‘Virtual Competition’, propose that anti-trust authorities should operate “tacit collusion incubators”. Given the success of incubators and agile methodologies in tech start-ups, it makes sense for regulators to harness intelligent technology to deliver smarter oversight.

Of course, large data firms (like social networks) could just be required to share the data they hold on individuals, proactively. GDPR requires service providers to enable “data portability”. But, taking the cue to use technical innovations, the growth in uptake of Blockchain technology may offer a solution.

With the benefits of automatic reconciliation, local copies and immutable copies of data held. This technology may be able to provide the audit trails needed for use-based regulation. Viktor Mayer-Schonberger, of Oxford University argues that not just the collection of data should be regulated, but also its use. That would be a major disrupter.

Education may be the secret to data democracy

One concern that is common across oil and data driven economies, is about unfair distribution of wealth and influence. “Data is labour” states Glen Weyl (from Microsoft and Yale University) and he suggests we need some kind of “digital labour movement”. People need to understand that their data has value, so they shouldn’t just give it away for free. Education and perhaps fines (post-GDPR) are needed to wake up people to the value being currently extracted by what some are calling the “Siren Servers” of Google et al.

A more equal geographic share in the value extracted by data will probably be even harder to achieve. Most big data ‘refineries’ are based in the USA or are controlled by US firms. Battles over privacy between Europe and America may well be a foretaste of things to come. Conflicts over oil have scarred the world for more than a century, I hope we do not see the potential for ‘data wars’ go the same way.

Addressing the challenges highlighted in this brilliant Economist article should be an urgent priority for the G7. Appropriate regulation, greater education and support for the innovation needed to build a more transparent data economy – may well be crucial to build a fairer economy for all.

I hope those reflections helped your journey, as either an entrepreneur or investor. If you’d like to hear more about our journey with Brainnwave, please do get in touch.